Digging for the future – a future archaeology

What could future archaeologists – archaeologists digging up the future instead of the past – tell us about the timeframe of change we are living? How could their speculative findings be a trigger for debate on future-oriented choices we face today? How could the aesthetics of the archaeological practice engage more diverse audiences more deeply in the shaping of positive futures ahead?

These were some of the underlying questions which set the design team of Pantopicon on a course to further explore the potential of the archaeological metaphor within the context of a design & foresight driven research and engagement strategy.

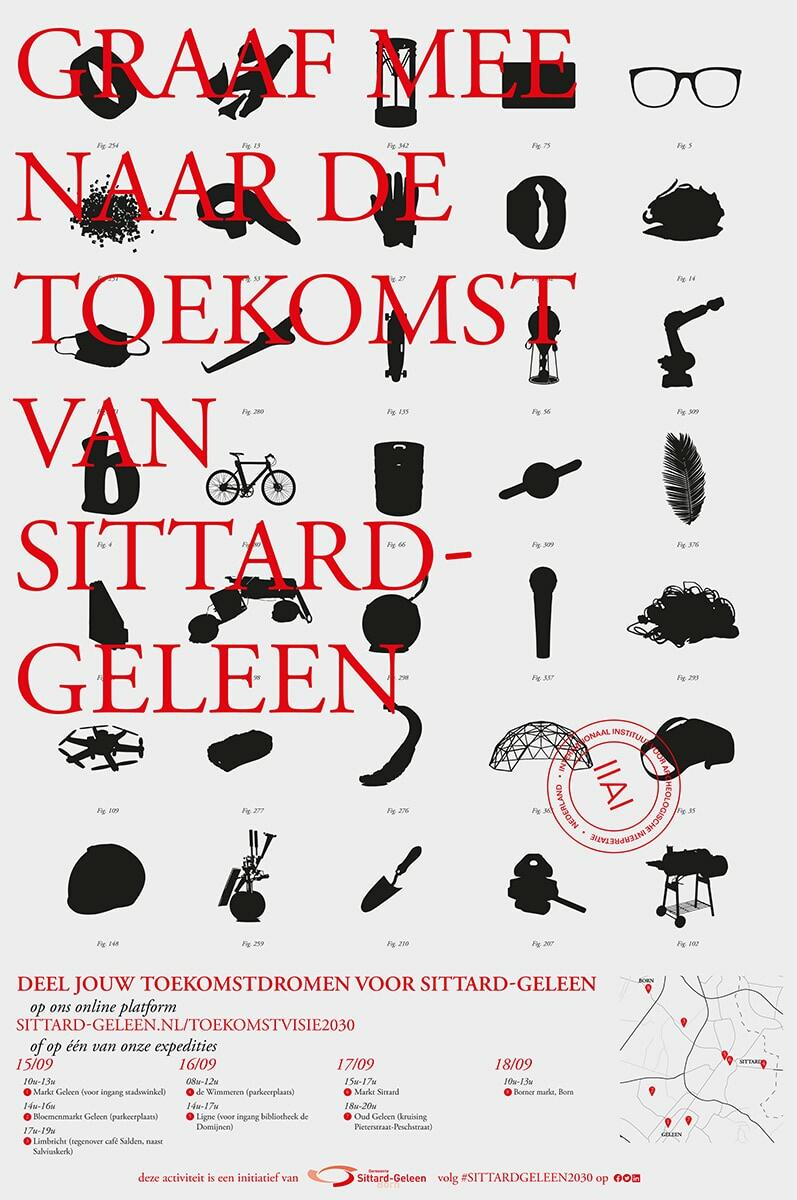

As a first instalment, a future archaeological experience was designed around speculative findings, fragments of a potentially future version of an existing city. The design team set up a fictional future-archaeological camp in the streets of the Dutch town of Sittard-Geleen, engaging inhabitants in discussions around the findings and how they could be building bricks for a future vision of their town.

Perspectives beyond the present

The way in which archaeology contrasts two eras – the past and the present – with one another, not only highlights differences and similarities, but also contextualises them. It aids in linking past and present by weaving together fragments of both realities, logically as well as empathically. By maintaining the time-travel metaphor, but replacing the past with the future, one can piggyback on this effect and see both future and present in a new light.

Imagine how findings from the future might make us see today in a different light. Think for example about how – now that we find ourselves well into the anthropocene – they might render the way we characterise the relationships between man, nature, artefacts, technology, science and the built environment seem archaic? Imagine how these findings from the future might perhaps embody “relationality” – rather than “the thing” or “the object” as the key organisational principle, of which all rationalisations and categorisations are merely a mystification? How might they perhaps make our present look unilateral, Western-centric and even paternalistic? How might future archaeological findings help us to see new options? How might they help us to de-colonise our gaze upon the future – creating new choices – by giving voice to other actors and perspectives?

These are all questions, not only central to contemporary debates within design, but also the world in general. In archaeology and its aesthetics we see a framework to catalyze the debate and include a broader range of voices in envisioning the future ahead by questioning un(der)acknowledged fragments and potentialities of both past and present in a new light.

Female protagonists & archaeological aesthetics

The general history of archaeology reads as if it were a particularly male history. Yet, upon a closer look, many women played crucial roles. Take for example Amelia Edwards, Hilda Urlin, Margaret Murray, Emilie Haspels and Freya Stark. Upon the latter, Virginia Tassinari – one of the designers on the Pantopicon team – came across as a child, as she was living in the same village in Northern Italy. Freya’s stories, together with her house full of archaeological findings and parafernalia from her adventurous and mythical trips in the Middle East (which Stark made memorable in her many travel books through her eyes as an insider) have always been a source of fascination and inspiration to Virginia. They are proof that even in the beginning of the 20th century, in the colonial and male-dominated Western civilisation, female emancipation and intellectual life were possible. After one century, Freya’s stories are still relevant and serve as a source of inspiration to seeing the future through fresh eyes, free from a Western-centric and paternalistic gaze that all too often are still pervasive.

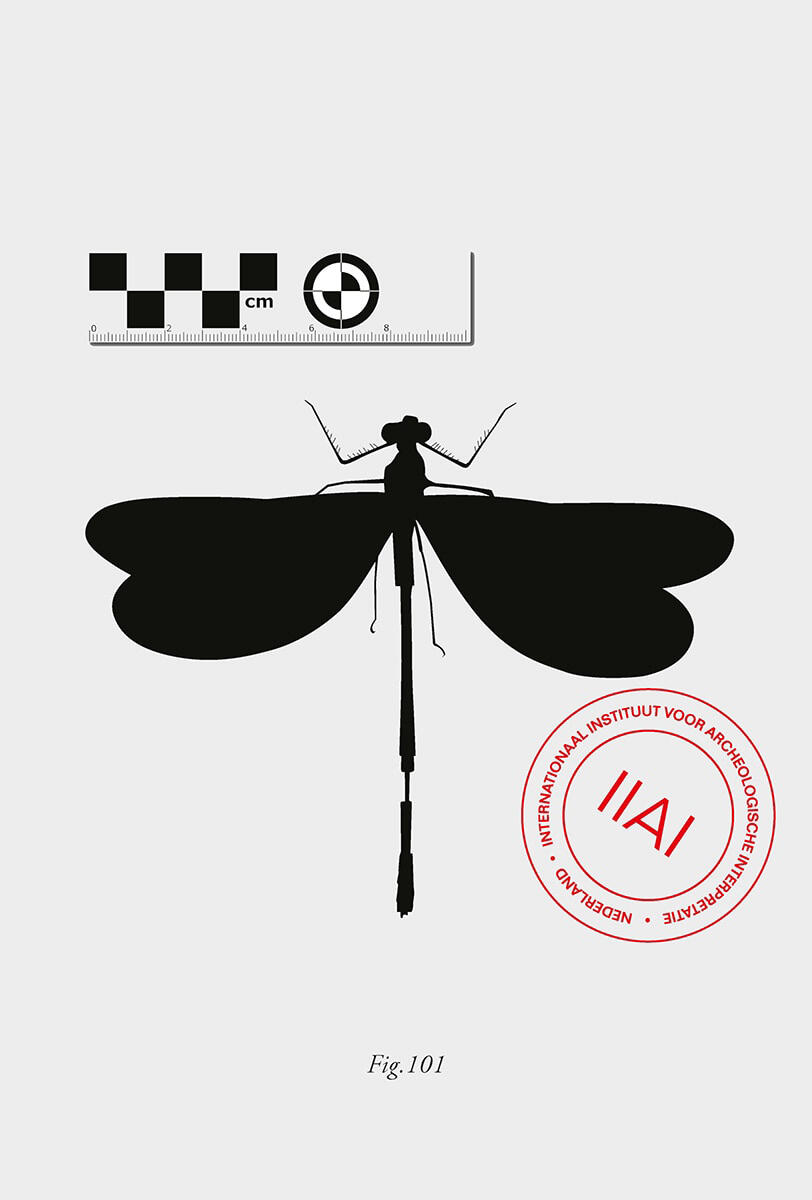

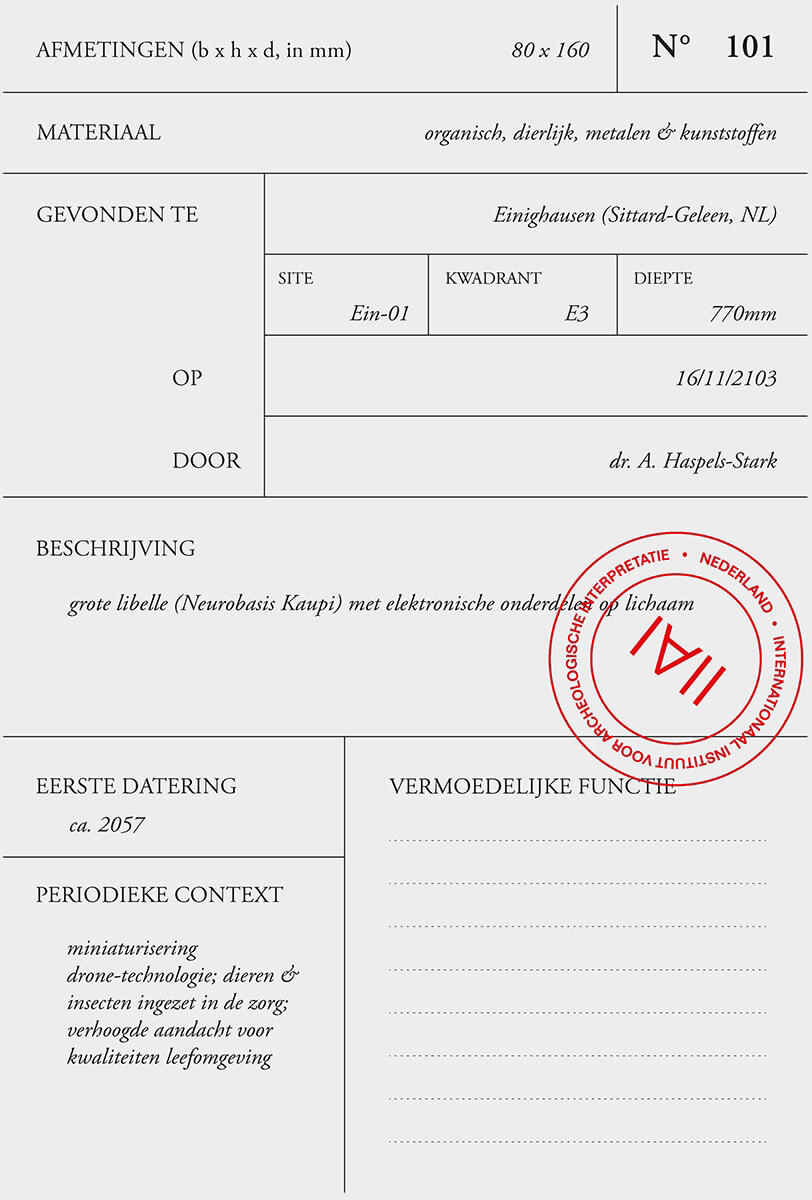

Most female archaeologists of the Victorian Age were not only excellent scholars and storytellers but often also skilled in very practical aspects of their work such as photography, illustration, translation and cataloguing. The way of cataloguing and inventorying their findings as well as repackaging them to spread and popularise knowledge and the field of archaeology as such, were crucial elements in moving archaeology out of its specialism into popular culture. This whole endeavour also came with a distinct aesthetics which the Pantopicon design team relied upon heavily in their design of a future archaeology experience.

It was these female archaeologists who inspired the team to create their first instalment of a future archaeological experience around a fictional, female protagonist, i.e. the archaeologist Amelia Haspels-Stark. Her name pays homage to three figures in the rich lineage of female archaeologists. Amelia’s quest and findings were inspired by potentially impactful future developments identified earlier on in the project. Inspired by the history and current reality of the place, and inspired by true archaeological findings in both content and form, Pantopicon’s team created a few dozen future findings. Each artefact, evocative of a potential future reality would be the result of a series of future developments shaping past or present potentialities. For example, the team envisioned and gave physical form to plants from a nature-inclusive neighbourhood, pipelines from a circular economy-driven industrial site, robotic insects monitoring air quality showing the blurring between the natural and the artificial, invitations to future citizen assemblies, etc. With respect to unearthing and “futurising” past potentialities, in the research – inspired by the likes of Freya Stark – attention was also paid to these artefacts and perspectives on life and the surrounding world that tend to escape mainstream interest or attention, that go beyond anthropocentric, Western-centric or male-centric views. The eventual selection of artefacts from the future, were presented in a way, reminiscent of the archaeological methods & aesthetics of the Victorian age female archaeologists.

Putting them on display as series of ‘conversation starters’ imbued with potential meaning and questions, Pantopicon engaged the inhabitants of Sittard-Geleen in a discussion about the past, present and most of all future of their municipality in all its dimensions. Passers-by were stimulated not only to aid in interpreting or contextualising the findings and giving them a place in a larger envisioned/imagined future that would appear in front of their mind’s eye, but also question them on the changing relationships between things like technology, nature, man, the built environment etc. The archaeological metaphor resonated particularly well with the inhabitants of the town, already home to a key archaeological museum in the region.

While stage-setting fictional excavation sites around town, presenting findings in fictional cabinets – inspired by the Victorian travel chests – in a kind of mobile Wunderkammer, bringing together naturalia and artificialia, the Pantopicon team – supported by members of the municipal organisation – played the role of future archaeologists helping Amelia to identify plausible meanings of the found artefacts. The performative setting, costumes included, would attract the attention of passers-by, who would be drawn into the storyline, being asked for help with the interpretation of the fictional archaeological findings.

Simultaneously a web-version was temporarily made available to trigger people’s attention, give them a glimpse of future findings they might expect to find and thus draw them into the metaphor of the experience.

Eventually, the travelling archaeological site will lead to the fabrication of further “speculative found fragments”, inspired by the conversations with inhabitants and their dreams and fears regarding the future of the town. These will be brought together in an on- and offline exhibition, in which the story of Amelia will further interweave itself with the lives and future narratives of the inhabitants. Hence, the future archaeology experience becomes an instrument for collaborative imagination and debate regarding the potential futures of the town and moments of choice and opportunity already presenting themselves today.